A few days ago, an article popped up on The New York Times titled How to Raise a Creative Child. Step One: Back Off. Attention grabbing, isn’t it? My first son, Parker, will be turning four this March and I’m starting to think about which musical classes I should enroll him in. (For sports, he’s already playing soccer and swimming.) How can I make him a well-rounded individual? Then there’s the ever present question, “Is he in the right pre-school?” Or the one I think about daily,”How can I foster his creativity?” On that last question, psychologist Benjamin Bloom provides some insight.

When the psychologist Benjamin Bloom led a study of the early roots of world-class musicians, artists, athletes and scientists, he learned that their parents didn’t dream of raising superstar kids. They weren’t drill sergeants or slave drivers. They responded to the intrinsic motivation of their children. When their children showed interest and enthusiasm in a skill, the parents supported them.

Whatever profession my two boys end up taking, I want my children to find happiness in what they’re doing. I want them to feel like they’re capable of changing the world, that the sky is the limit for them, that no obstacle is too difficult to overcome. Am I a dreamer? Maybe. But what is our role as parents if we can’t provide a supportive, nurturing environment?

Why is creativity so important you may ask? I think in any profession, whether your son or daughter becomes a lawyer, doctor, or artist, you want to give them the encouragement they need to excel. Also, in this global economy, it’s the creative minds that will become the leaders in this world, the ones that will not just accept the status quo but will challenge it to make the world a better place.

Here are a few more paragraphs I liked from the article:

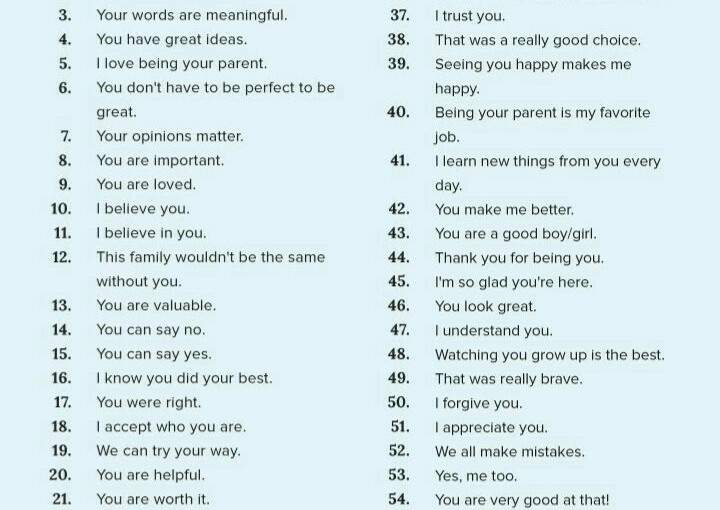

So what does it take to raise a creative child? One study compared the families of children who were rated among the most creative 5 percent in their school system with those who were not unusually creative. The parents of ordinary children had an average of six rules, like specific schedules for homework and bedtime. Parents of highly creative children had an average of fewer than one rule.

Creativity may be hard to nurture, but it’s easy to thwart. By limiting rules, parents encouraged their children to think for themselves. They tended to “place emphasis on moral values, rather than on specific rules,” the Harvard psychologist Teresa Amabile reports.

Even then, though, parents didn’t shove their values down their children’s throats. When psychologists compared America’s most creative architects with a group of highly skilled but unoriginal peers, there was something unique about the parents of the creative architects: “Emphasis was placed on the development of one’s own ethical code.”

Yes, parents encouraged their children to pursue excellence and success — but they also encouraged them to find “joy in work.” Their children had freedom to sort out their own values and discover their own interests. And that set them up to flourish as creative adults.

On a side note, months ago, my mother-in-law told me about how Albert Einstein credits playing violin in helping him come up with ideas on relativity. It’s a great lesson as to why we should support our children’s creative endeavors.

No one is forcing these luminary scientists to get involved in artistic hobbies. It’s a reflection of their curiosity. And sometimes, that curiosity leads them to flashes of insight. “The theory of relativity occurred to me by intuition, and music is the driving force behind this intuition,” Albert Einstein reflected. His mother enrolled him in violin lessons starting at age 5, but he wasn’t intrigued. His love of music only blossomed as a teenager, after he stopped taking lessons and stumbled upon Mozart’s sonatas. “Love is a better teacher than a sense of duty,” he said.

Now to foster love.

Art, called “He Gave Me The Brightest Star,” by Adrian Borda.